Every day Yazli ý went out with scythes

to cut fodder for the sheep. Once in our searches for the best, most succulent

grasses we wandered far off to the distant melon fields.

Yazli Uncle Djakul, the one with the devil's

wheel, was in charge of watching over the fields.

For some reason Djakul-aga was sitting outside

in front of the cabin, lthough the sun was adready scorching.

"Quit!" he whispered as we tossed our sacks

down and approached. "There's a snake in the cabin! It looks as though

it's trying to give someone the slip. Sit here quietly, and we'll see what

happens."

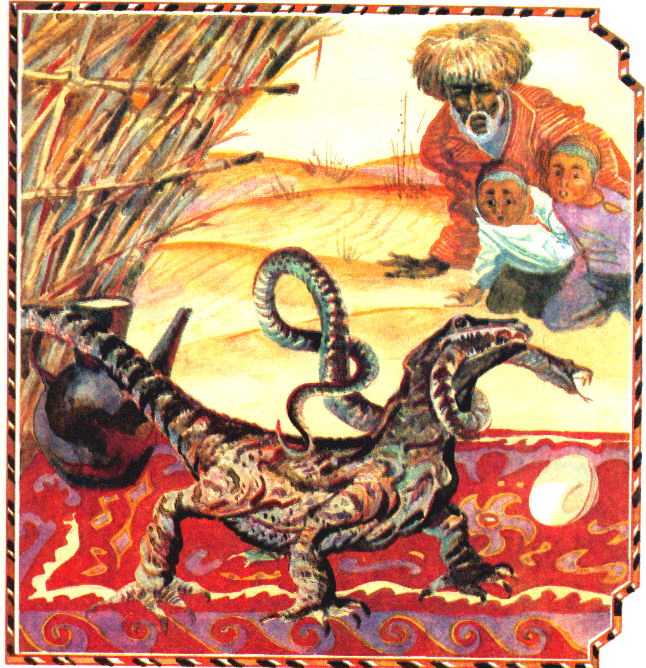

Djakul-aga was right: as we watched, a giant

lizard went scuttling into the cabin, hissing menacingly. The snake thrashed

its tail and darted off, but the lizard grabbed it and began dragging it

away. We followed quietly behind. The lizard sunk its teeth into the snake's

back and killed it. And then it noticed us. It tried to run away, but we

caught it and used some string to tether it to a peg like a calf. Then

we tossed it some meat and watched as it devoured it.

Djakul-aga left for the collective farm

office and we lay in the shade of the cabin, feasting on ripe melons and

watching the lizard, waiting to see how it would try to break loose from

its tether. Suddenly yet another lizard came charging out from behind the

sand dune. It lunged at the lizard on the tether, butted it in the side,

and darted off.

We rushed over to help our lizard; blood

was gushing from its wound. We carried it home, put iodine on the wound,

and put it underneath a box. Both we and the grown-ups fed it ten times

a day. Soon the lizard recovered. Now, we thought, it would be our pet,

but as soon as we lifted up the box the lizard darted off into the grass,

turning to snap its jaws viciously at us before disappearing from view.

Our parents found a serious pastime for

Yazli and me. Now we too were herders, like my father. True, our livestock

was a bit smaller in scale- goats and sheep. And there were less of them-seventeen

heads in all. After school we would drive our herd along the same path

that my father used. And like real shepherds, we always took some food

along: chureks or some melon. We even had our own equipment: Yazli had

a compass, and I had a penknife with a bird carved on the handle. And of

course we had our shep-herd's crooks.

We would drive our flock into the "jungle"

- the thickets along the riverbanks. Succulent grasses grew beneath the

licorice and tamarisk bushes.

The river was our ally; it was impossible

for our clever goats and sheep to cross, but all the same we spent a lot

of time searching for strays. Once we returned without a ram called Churmenek.

Our efforts to find him in the near vicinity had failed, and with night

approaching we were afraid to go looking for him in the "jungle". We drove

the flock in the dark, talking in deliberately loud voices even though

we walked shoulder to shoulder. This way we hopped

to frighten off any wild animals.

The next morning I stayed home from school.

I climbed on the donkey and went to search for the missing ram. Churmenek

had gotten his hind legs entangled in the cat's-tail stalks. when I finally

found him he was lying awkwardly with his head down, barely breathing.

The area surrounding the bush was covered with jackal prints. It looked

as though Churmenek had thrashed about furiously, trying to get himself

untangled, and the cowardly jackals had been too afraid to attack. I cut

the stalks off at the roots and drove the ram out onto the clover. I knew

I wasn't supposed to do it, but after having lived through such a terrible

night, I thought that Churmenek deserved some sort of reward.

After eating his fill, Churmenek went charging at the

makeshift cabin Yazli and I had built from licorice stalks and rammed into

it with such force that it collapsed instantly.